“This is the worst piece of cheek of all.”

Earlier this week, a new book gave us a glimpse of the heart-warming fan mail Mark Twain received over the course of his career. But for every person who showered Twain with genuine and unconditional gratitude, there seemed to be a dozen demanding a range of outrageous things — the curse that comes with the blessing of inhabiting the public eye as a national celebrity. And while the art of asking without shame remains essential and commendable, some of the audacious requests Twain received, collected in R. Kent Rasmussen’s excellent Dear Mark Twain: Letters from His Readers (public library), merit a scowl or at least a scoff for their sheer impudence. Here is a small sampling.

Earlier this week, a new book gave us a glimpse of the heart-warming fan mail Mark Twain received over the course of his career. But for every person who showered Twain with genuine and unconditional gratitude, there seemed to be a dozen demanding a range of outrageous things — the curse that comes with the blessing of inhabiting the public eye as a national celebrity. And while the art of asking without shame remains essential and commendable, some of the audacious requests Twain received, collected in R. Kent Rasmussen’s excellent Dear Mark Twain: Letters from His Readers (public library), merit a scowl or at least a scoff for their sheer impudence. Here is a small sampling.

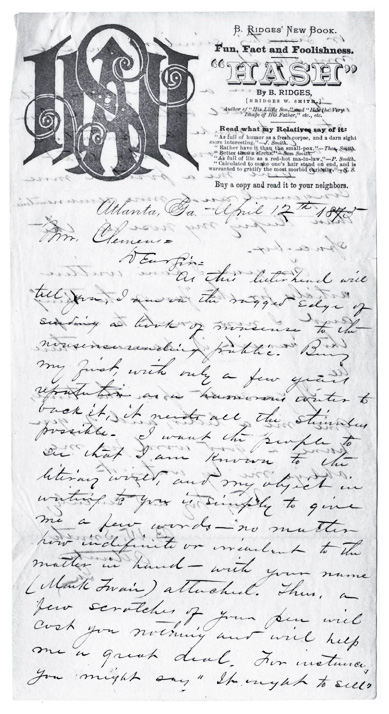

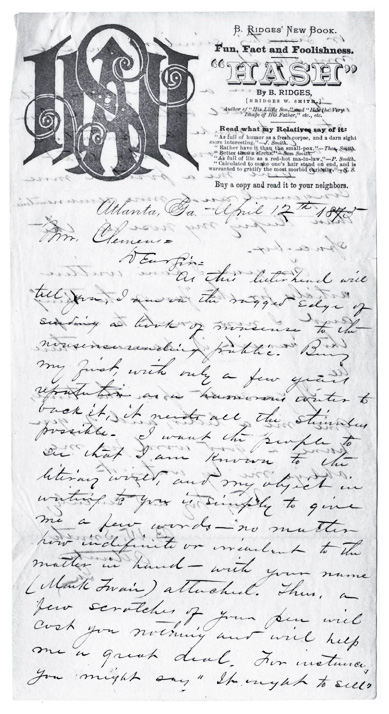

Letters requesting endorsement were not uncommon, but on April 12, 1875, Twain received one of particular absurdity from a Goorgia “journeyman printer” by the name of B. W. Smith:

Mr. Clemens —

Dear Sir —

As this letterhead will tell you, I am on the ragged edge of sending a book of nonsense to the nonsense reading public. Being my first, with only a few years reputation as a humorous writer to back it, it needs all the stimulus possible. I want the people to see that I am known to the literary world, and my object in writing to you is simply to give me a few words — no matter how indefinite or irrevelent to the matter in hand — with your name (Mark Twain) attached. Thus, a few scratches of your pen will cost you nothing and will help me a great deal. For instance, you might say “It ought to sell” or something similar — You see my object –

First page of letter from B. W. Smith. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

A number of the letters were preserved with Twain’s comments. On this one, he scribbled:

From some unknown person who probably has brains & modesty in about equal proportions.

Solicitations for feedback were equally bountiful. In a lengthy letter from November of 1875, an Alabama woman by the name of Louise Rutherford asked:

Sir:

I have written a book and can’t get it published. What, do you suppose, is the cause of my failure? It is a novel — the book I mean — and is sensationally perfect. In fact, it is so far ahead of most of the “roughing it” species of publications, that I am amazed beyond mea sure, at the refusal of the publishers to issue it. How did you manage to get your first work before the public? It is a “dark and bloody mystery” to me; and I would like you to explain. Perhaps if you let me into the secret I may succeed with mine.

[…]

I plead guilty to being romantic; but I believe I am more ambitious than romantic; and I wish you would help me with a little advice about my book. I am not able to pay beforehand, for its publication, and I don’t know whether I could do anything with it, unless I had money. Can I, do you think? Please be so obliging as to tell me. I have no friend who is informed in such matters.

Twain’s comment:

From a muggins in Alabama.

Though clearly self-aware of his audacity, this 18-year-old boy writing Twain in May of 1876 was anything but self-conscious about it:

Mr. Clemens,

Dear Sir,

I am going to make bold to ask of you a great favor. I wish to publish a small sheet, say, about 16×22 inches — divided into four pages of three columns each.

And I wish your permission to use the title (Mark Twain) as editor. I want you to furnish such matter as would in your own opinion, be suitable, for such a paper, as I wish to have this filled with your fun and sentiment. I, shall, if you oblige me, sell them at Philadelphia, this summer, and I assure you that everything shall be conducted in such a manner as you would agree to. There shall be no advertisements in the paper — but all space shall be filled with reading matter. Paragraphs can be selected from other Authors, which will lessen your labors, somewhat. The matter need not of necessity, all be fresh, but of course you will use your own judgment in that matter.

I am aware that in presuming to ask such a favor of you, since your time must be so completely occupied that I am rather audacious, and perhaps, impertinent. . . .

I will allow you what remuneration you consider just and right, either paying you a certain sum at the start or allowing you a percentage on the sales —

If you think it best and necessary I will come to Hartford and see you, about the plan. I hope and trust that you will grant me this favor, and greatly oblige,

Your Obedient Servant

Charles. S. Babcock.

Twain’s comment:

From a muggings

In November of 1879, Twain — born Samuel Clemens — received one of many frequent requests to explain his pseudonym:

My dear Sir

Will you have the goodness to send me as fully as you may be able the history of y’r pseudonym –“ Mark Twain.” How it was originated when you first used it, & in what connection on all these points I sh. be exceedingly glad to be informed.

I am preparing a handy book on pseudonyms — to include the history of the more important ones — wh. the Harpers are to publish — and it is extremely desirable th. I have the information for wh. I ask. With the hope th. I am putting you to no great inconvenience

Believe me Dear Sir

to be faithfully:

Rev. J. Dewitt Miller

Though he tended to generally ignore such inquiries, Twain was particularly annoyed by this one, due in part to its tone of especial entitlement and in part, no doubt, to its vexing abbreviations. His irritated comment:

From an ass — Not answered

In August of 1870, a moderately successful Canadian humorist asked:

Mr Clemens

Dear Sir, —

What will you charge to write me a lecture. One that will take about 1 ¼ hours to deliver it. Humorous and stirring, but not too pathetic. An early answer will very much oblige

Yours Respectfully

R. T. Lowery

Petrolea Ont Can.

Twain wrote in the margin:

Ass.

Autograph solicitations were among the most common requests, which Twain found invariably annoying — but hardly so much so as this laconic yet entitled one from an Iowa man named Clarence E. Ash:

Samuel Clemmens

Dear Sir,

The favor of your Autograph is respectfully solicited.

Twain couldn’t curtail his irritation, scribbling in outrage:

Good God!

In March of 1875, he received the following behest:

Mr. Sam Clemens

Dear Sir:

A few young people in town are about forming a literary club, and as we cannot decide upon a name, it was proposed that I should write to you and ask your advice.

The object of the club is improvement combined with pleasure.

At our meetings we have an entertainment about an hour long, consisting of declamations, readings, music &c., and then the rest of the evening is spent in social amusements.

Several names have been proposed, but we cannot find an appropriate one.

If you will help us out, provided it does not inconvenience you too much, we shall feel greatly indebted to you

Very truly yours,

S. P. Moor house

Sec.

Twain, suspecting the letter was an autograph grub masquerading as an already audacious request, jotted a comment:

This is the worst piece of cheek of all.

Such autograph ploys were, in fact, quite common. In November of 1901, Twain received the following short letter:

Dear Mr. Mark Twain: —

I am a little girl six years old. I have read your stories ever since they first came out.

I have a cat named Kitty, and a dog named Pup.

I like to guess puzzles. Did you write a story for the Herald Com-pe-ti-tion?

I hope you will answer my letter.

Yours truly,

Augusta Kortrecht.

Observing the mature handwriting, Twain commented unforgivingly:

Lame attempt of a middle-aged liar to pull an autograph.

Some of the most common requests Train received were for loans, ranging from the naive to the auspiciously audacious. In 1874, for instance, he received a letter from a woman who signed as Mrs. Mary Margaret Field. She outlined her financial problems plaguing her life of relative privilege, even noting she still owns a fair amount of valuable assets and real estate, the asked Twain for a one-hundred-dollar loan:

I write to you, because I have read sketches of yr life, and it seems to me, that, as you have raised yourself from obscurity and poverty, by your own talents and energy, you may feel some interest in the struggles of a Woman, who has supported herself, entirely, creditably, and honorably, by her pen.

[…]

I cannot tell you how earnestly I pray that your heart may be moved to assist me. — In your happy home, — wealthy, fortunate, famous and beloved, as you now are, you may have forgotten the old days of struggle. — Yet call them up once more, for a moment, to your mind, & for their sake, & because of the knowledge of suffering they gave you, have compassion on me, — for indeed, my distress is very deep, & genuine, and I know not which way to turn for relief.

Twain rarely responded to these letters, but when pushed beyond the limits of his irritation-tolerance, he did — and he did with fierce comedic bile:

Madam: Your distress would move the heart of a statue. Indeed it would move the entire statue if it were on rollers. I have seen looked upon poverty & its attendant misery in many lands, & in my own person I have suffered in this sort: but I never have heard of a case so bitter as yours. Nothing in the world between you & starvation but a lucrative literary situation, a few diamonds & things, & three thousand seven hundred dollars worth of town property. How you must suffer. I do not know that there is any relief for misery like this. Suicide has been recommended by some authors.

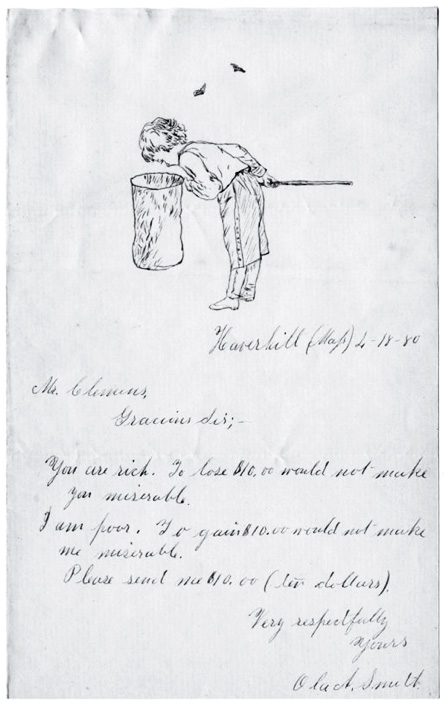

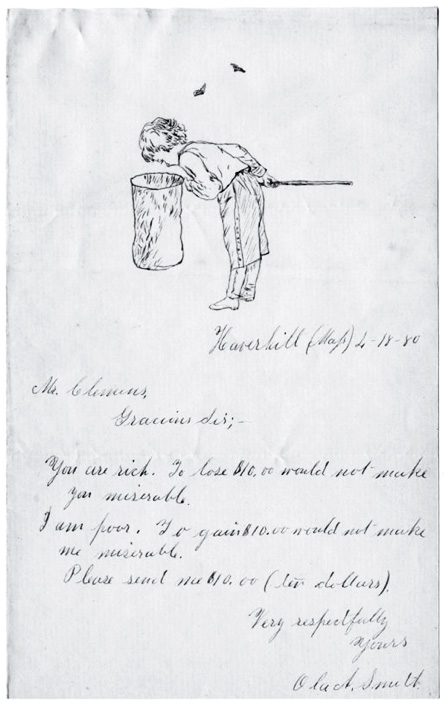

Letter from Ola A. Smith. Courtesy of the Mark Twain Papers, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In April of 1880, a Massachusetts spinster named Ola A. Smith made a similar request, far more modest in both sum and word count, yet doubly entertaining in its blend of “logical” reasoning and witty audacity:

Mr. Clemens,

Gracious Sir; —

You are rich. To lose $10.00 $ 10.00 would not make you miserable.

I am poor. To gain $10.00 $ 10.00 would not make me miserable.

Please send me $10.00 $ 10.00 (ten dollars).

Twain’s comment:

O my!

Dear Mark Twain is just as delightful in its entirety. To fully appreciate the era’s epistolary charisma, complement it with this vintage guide to the etiquette of letter-writing from the same period.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings takes 450+ hours a month to curate and edit across the different platforms, and remains banner-free. If it brings you any joy and inspiration, please consider a modest donation – it lets me know I'm doing something right.